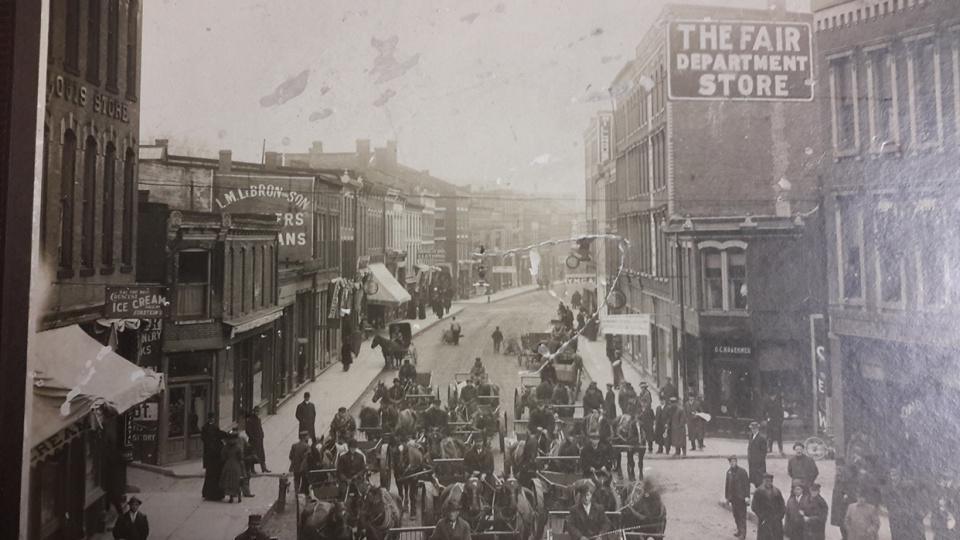

Perhaps Galena’s most colorful decade was the 1840’s. The new market created by the rising farm population, the steady growth of the city itself, and the continued increase in lead production, all made for free spending. The four-story buildings along Main were crammed with merchandise to be distributed throughout the Old Northwest Territory.

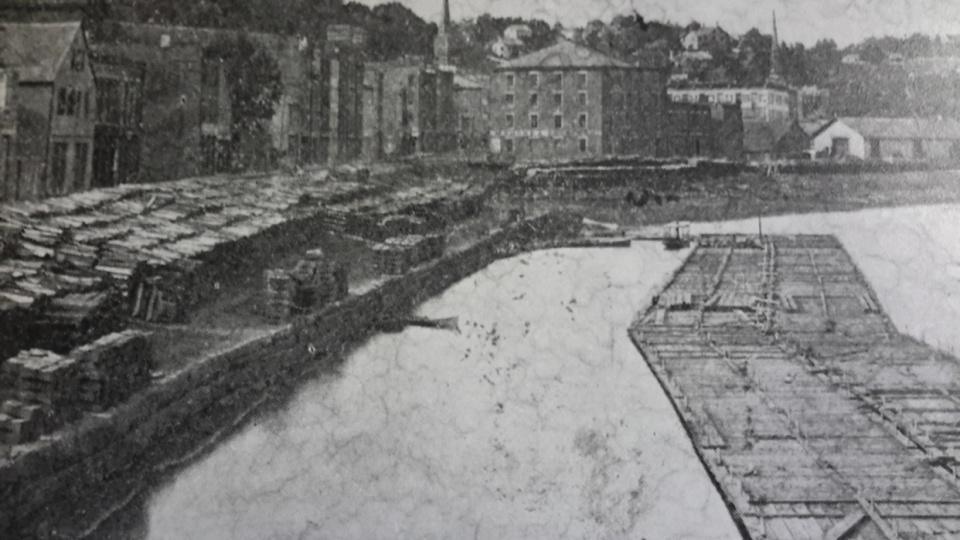

Boats raced for the limited dock space, sometimes settling a dead heat by a knock-down and drag-out brawl on the wharf.

Lined up in front of the levee stores was usually a “steamboat supply house,” dealing in cable chains and ropes, steamboat anchors, block and tackles, steam pipes, and whatever the boats needed.

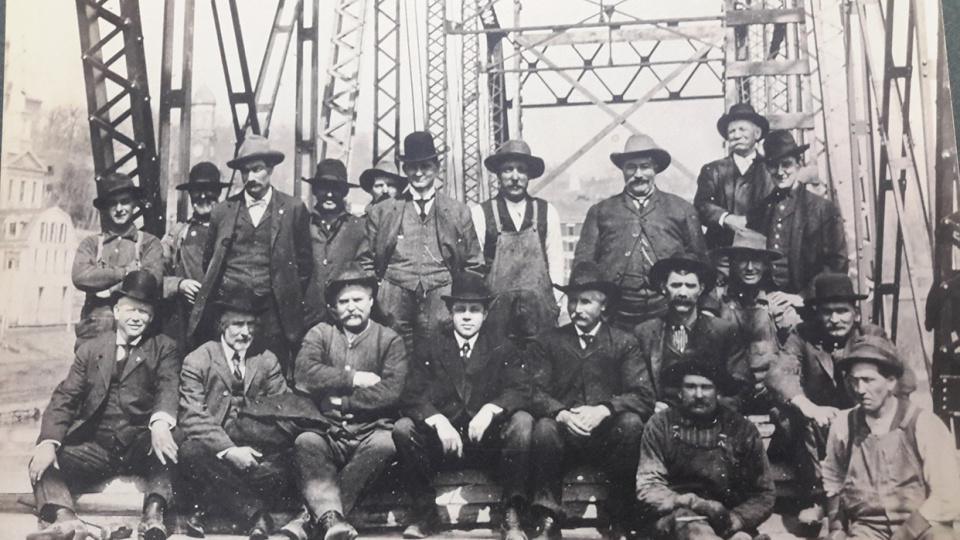

Toll bridges were built, one at Bouthillier Street and another at Franklin, but were so frail that both were swept away in a flood the following spring. Ferry service had no competition until 1847, when new toll draw-bridges were built by private capital at Meeker and Spring Streets. Shortly after, the city bought these and made them public.

By 1845 the population had ballooned to over 8,000. The streets were crowded with rollicking, boisterous miners, farmers, and immigrants of all kinds.

Galena was still recognized as being the most important commercial point north of St. Louis. Some impressive statistics attest to the continued importance of the lead industry. Production peaked at 55 million pounds, but declined rapidly after 1847. By then farming products exceeded the value of lead. In this peak year, the mining district, with Galena as its hub, produced almost 85% of the nation’s lead, shipping 27,000 tons of lead on the Fever River!

After lead mining had peaked in 1845, gold was discovered in California in 1848, and many lead miners joined the California Gold Rush leaving Galena behind them. The little river continued to silt in and the large steamboats were increasingly unable to make their way into town. Further trouble came with the Illinois Central Railroad, which arrived from Freeport in 1854. At first it increased the trade of the city, but soon it siphoned off that trade to other towns, especially Chicago.

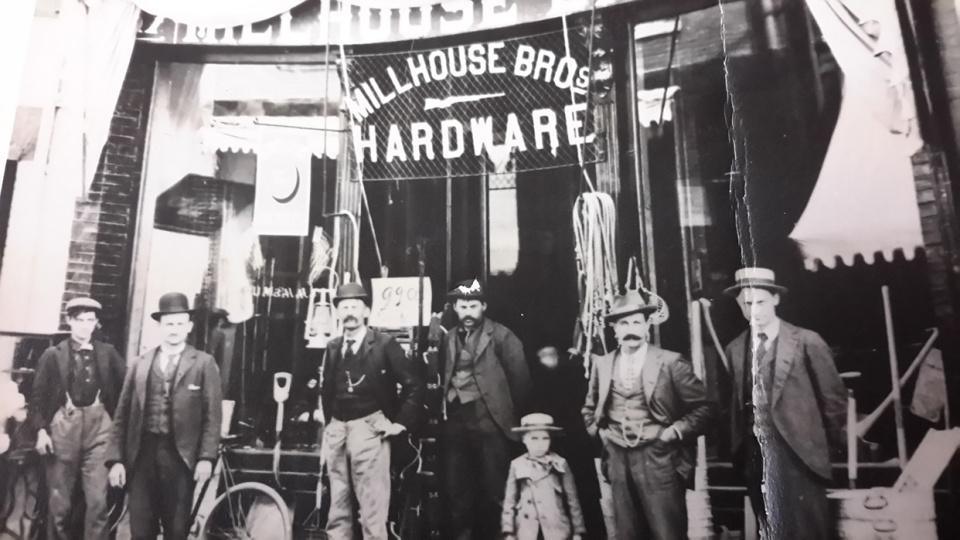

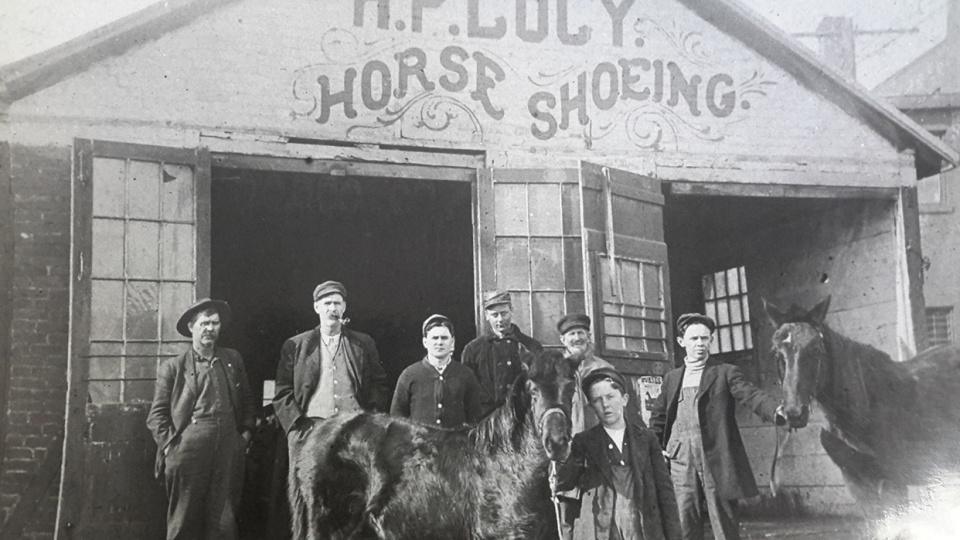

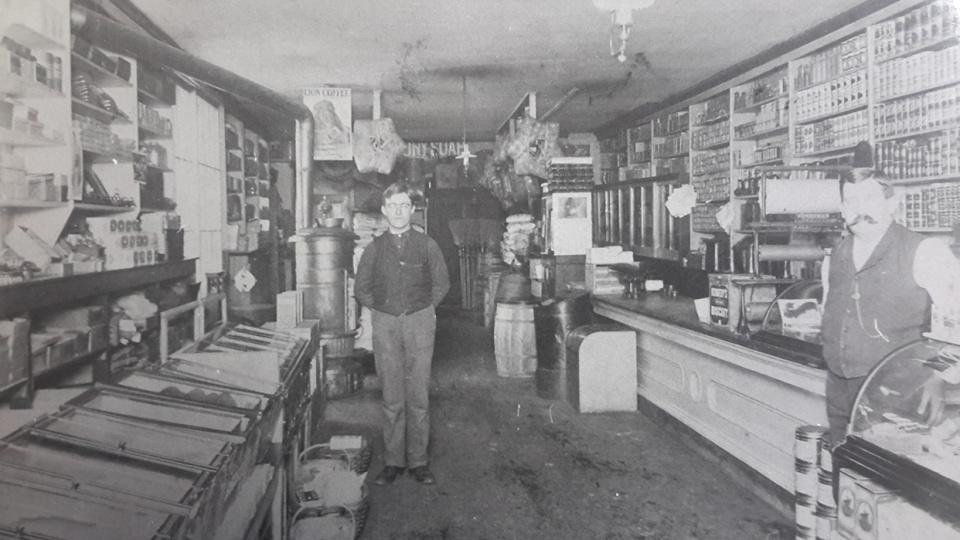

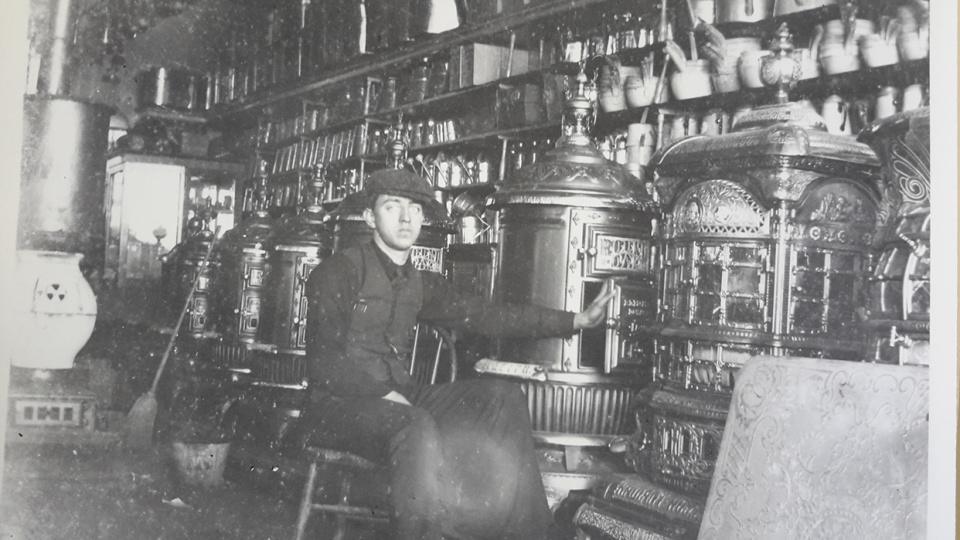

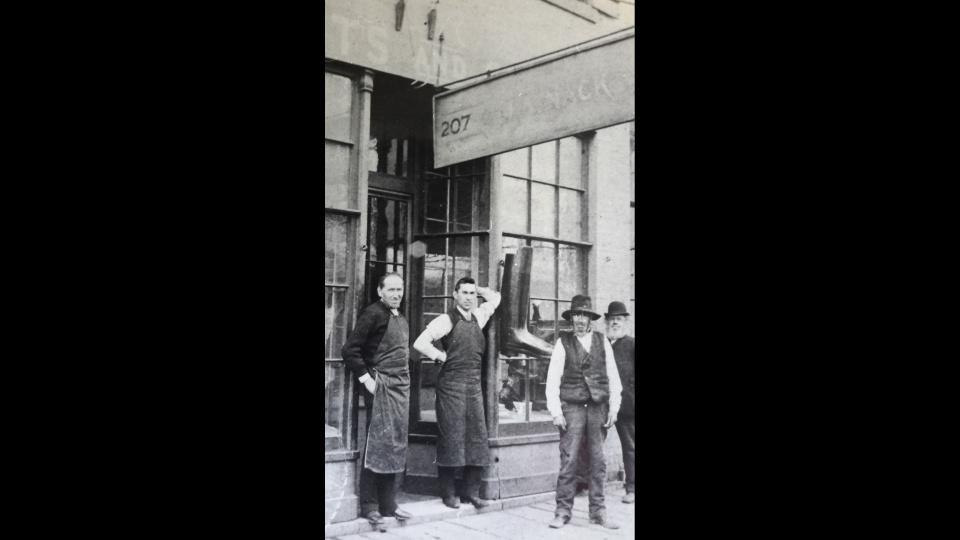

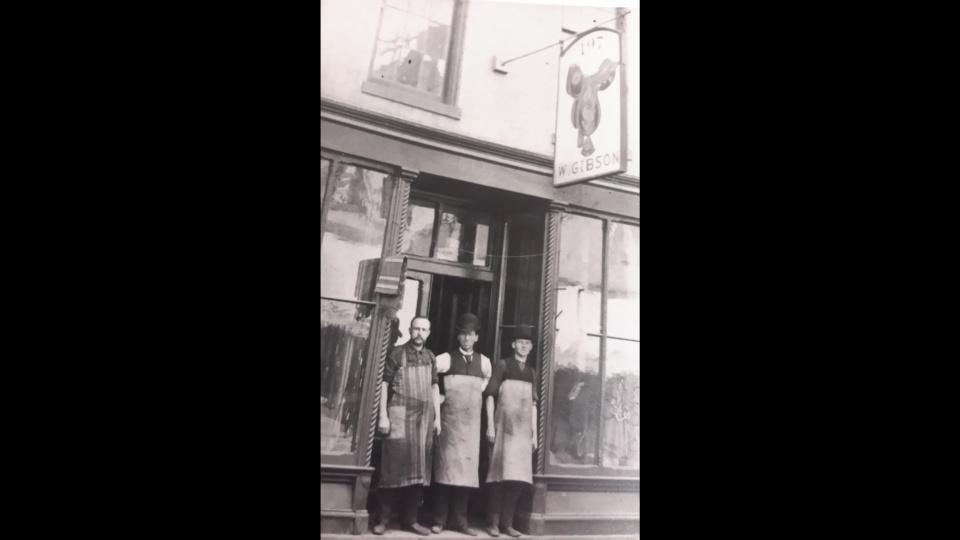

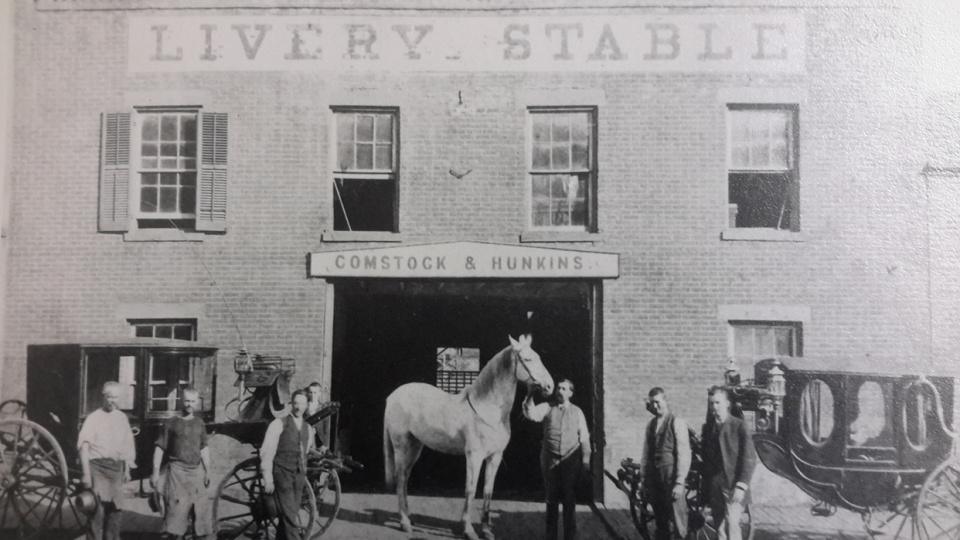

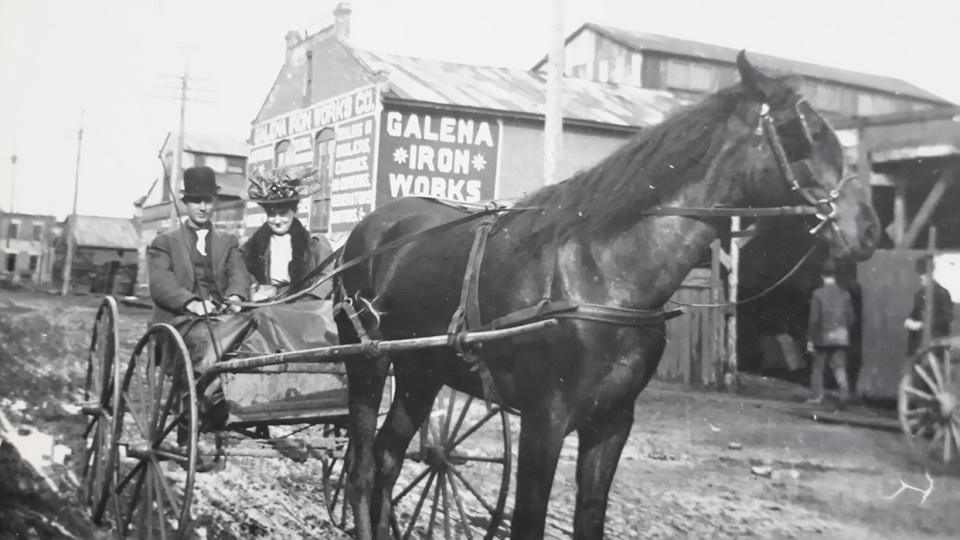

Between the mid-1840’s-50’s Galena’s bustling business community was prospering but undergoing many changes. According to Carl Johnson, in his book The Building of Galena: An Architectural Legacy, Galena had available a wide range of businesses and services. They included 2 daily newspapers, 2 grist mills, brick and lime kilns , a brick yard, 12 boot and shoe makers, 7 breweries, 2 plow factories, 1 leather store, 2 furniture factories, 4 tinners, 13 tailors, 1 potter, 4 watchmakers, 4 saddle and harness makers, 8 livery stables, 3 leather finishing houses, 12 blacksmiths, 2 carriage factories, 6 wagon makers, 5 apothecaries, 20 physicians, 2 gunsmiths, 12 cabinet shops, pottery plants, 2 confectionaries, 2 cooper shops, 3 auctioneers, 3 hardware stores and iron dealers, 3 soap and candle factories, 2 iron foundries and machine shops, 27 wholesale and retail dry goods houses, and 34 retail grocery and provision stores.

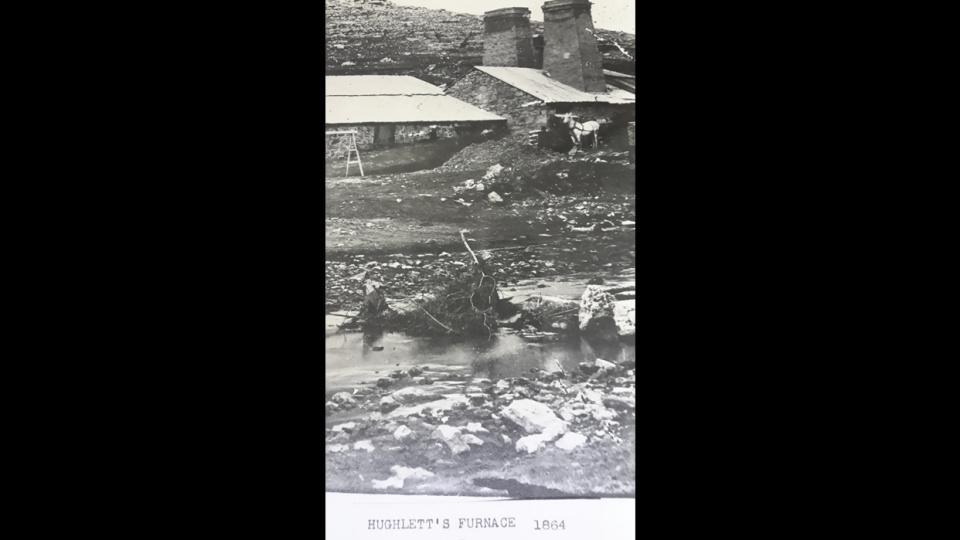

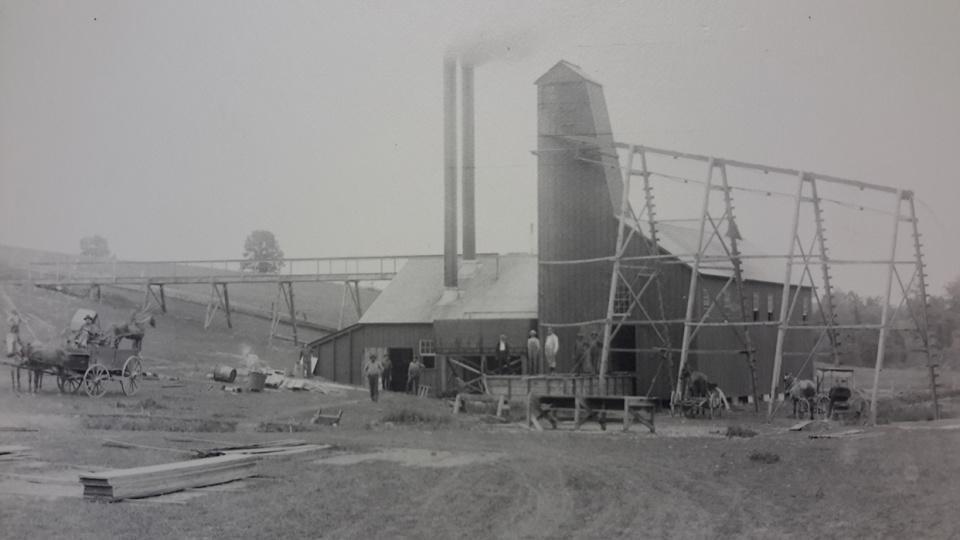

Two lead furnaces smelted 15,000 pounds daily. The best known was Samuel Hughlett’s, located on a small stream only a half mile from the end of Gratiot Street, now Dewey Avenue. (You will learn more about Hughlett on the Main Street Tour.)

There were also sawmills and several lumber yards. The mills in Galena were fed by large rafts of pine logs coming down from the Wisconsin “pineries.” John Collins gives a vivid portrayal of men who worked in the lumber industry in his book, Across the Plains in ’64. The loggers and pinery men, the “Lumber Jacks,” spent the winter in the woods, cutting and banking logs. When the ice went out, the logs were lashed in long narrow rafts and taken down the current to the Mississippi River, and then on down to the mouth of the Fever River. At the mouth of the Fever River, the field of logs was again broken into smaller rafts and slowly worked up against the sluggish current of the Fever River to “Old Town,” where they were delivered to the small steam powered saw-mills.

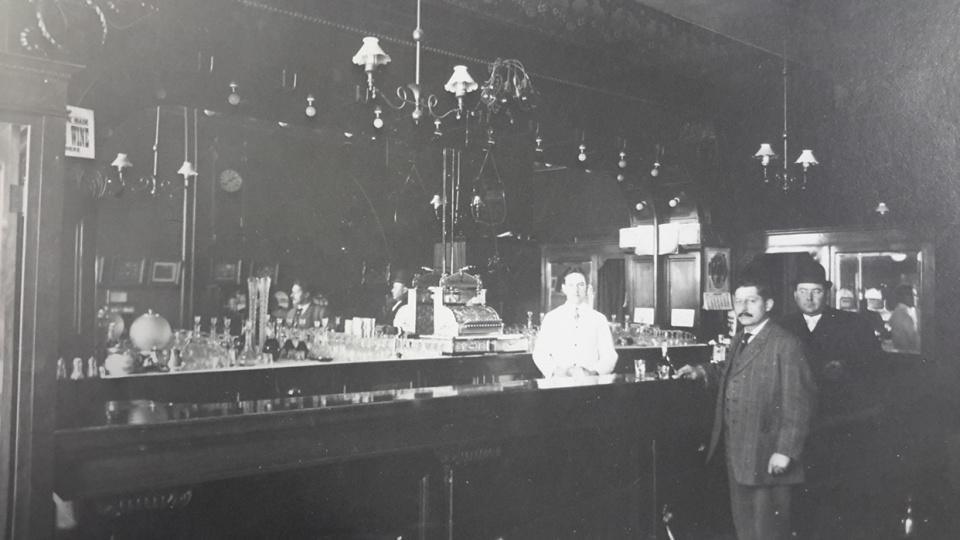

When the rugged loggers, who had not been out of the woods for nearly a year, reached Galena, they found the paymaster, who called off their names and handed each one a year’s wages.

This was not an event of little importance to every merchant and business man in town. Business was brisk, but so, too, was the thirsty appetite of the loggers for strong drink. Mayhem often followed.