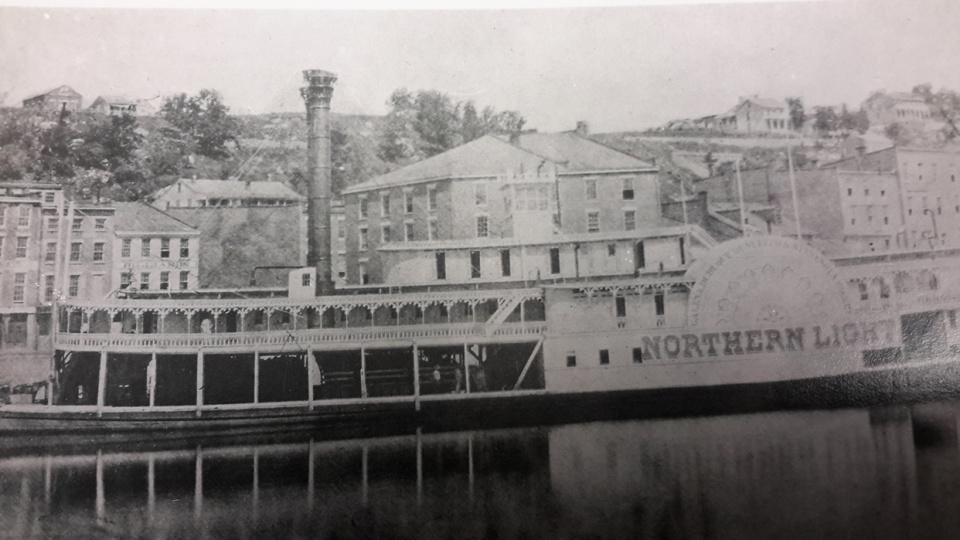

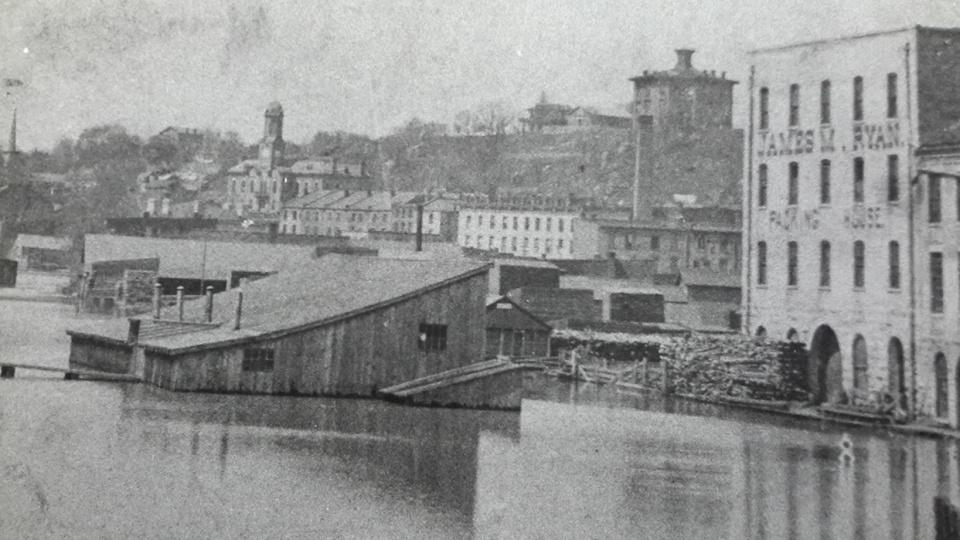

Galena’s days, like those of the keelboat, were numbered. As early as 1848, a Galena editor had pointed out that the Fever River must be improved or other cities would get Galena’s trade. The rapid flow of settlers into the Upper Mississippi Valley was calling for larger steamboats, and it was becoming increasingly difficult, if not impossible, for steamboats to squirm up the narrow Fever River.

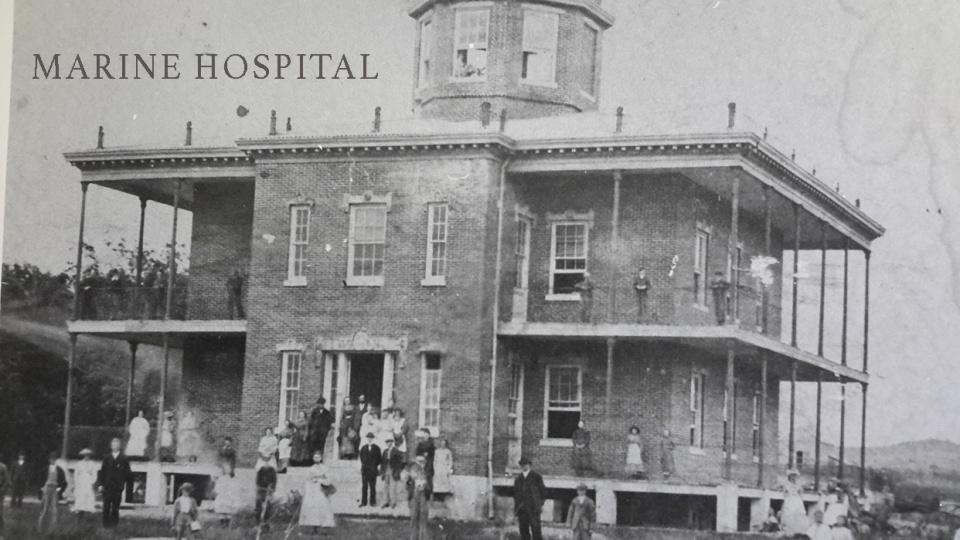

Still, with the wealth generated by the town’s huge trade, construction was booming. Distinguished mansions were popping up throughout the hillsides. These impressive homes were a reminder to all of each owner’s success and wealth. They were owned by bankers, merchants, and steamboat captains to name a few. Anyone who was wealthy enough to own a home of this size would also employ several servants and stablemen to keep the house running. Many of these homes had coach houses for horses and carriages, and servants’ quarters were located up separate staircases. Other changes included new churches and banks. A Marine Hospital was built along the Fever River, and gas street lights were installed and lined the streets.

One business, a leather goods store owned by the father of Ulysses S. Grant and run by Ulysses’ two younger brothers, was doing a booming business. In 1860 Ulysses would bring his family up the Mississippi from St. Louis to join his father and brothers, only to leave for the Civil War a year later.

In 1851 Congress approved a Land Grant for the construction of the Illinois Central Railroad which was to go through Galena. Galena was asked to relinquish land for a station and build a railway bridge across the river. The town fathers believed that a railroad bridge across the Fever River near the downtown area would be a hindrance to the river traffic. They seemed to feel that the town could not be both a rail center and a major river port; since many of these men had major investments in steamboat lines and other river-oriented commercial enterprises, they “chose” the river over the railroad. As a result, the Illinois Central ultimately made Dunleith (now East Dubuque), rather than Galena, its terminus east of the Mississippi—and later the railroad built a bridge to Dubuque, Iowa. Thus, the freight trains made their way through to Dubuque, 15 miles northwest, which soon became the busy metropolis that Galena could have been.

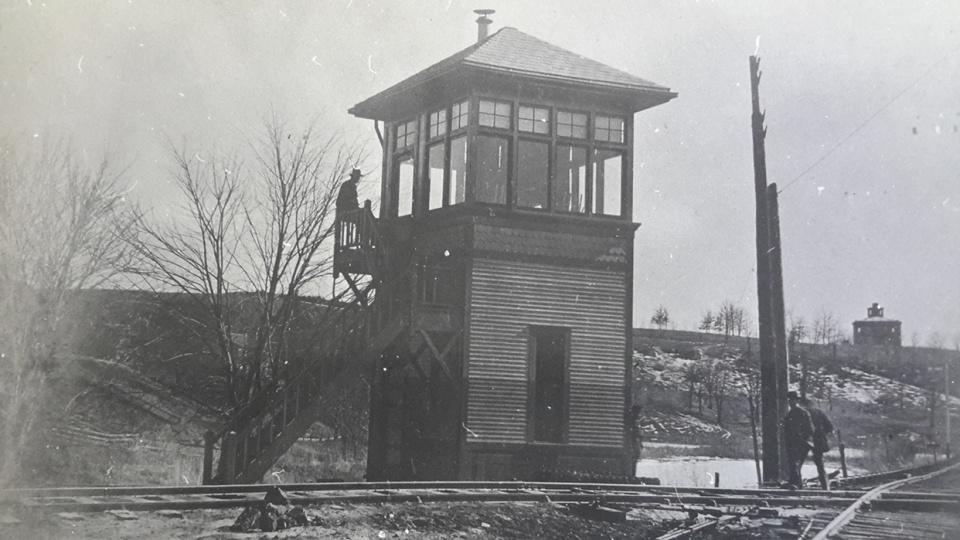

However, the railroad did make its way to Galena, and the railroad bridge was built.

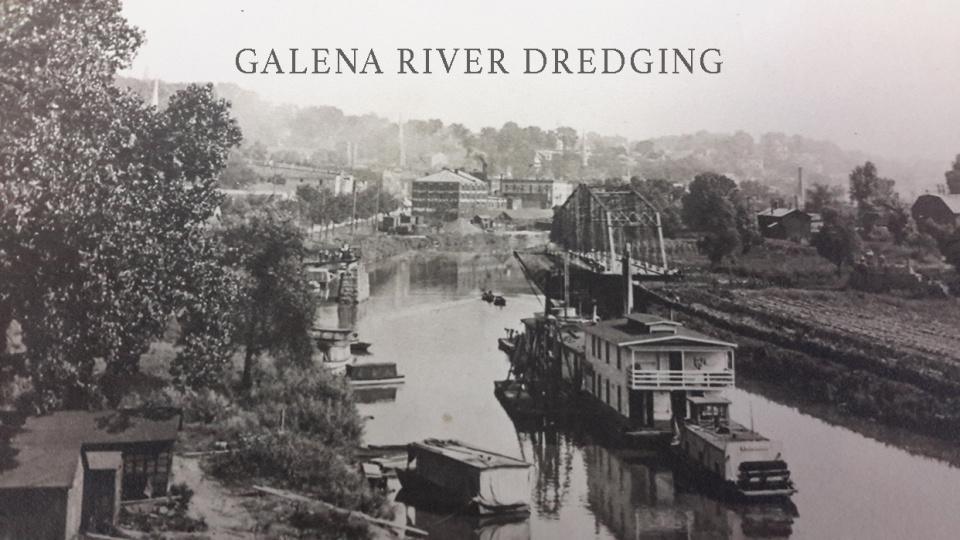

It was during this time that the renaming of the Fever River was being discussed. Local merchants worried that people might associate the name with scarlet fever and thus be reluctant to settle here. Therefore, in 1853 the river was officially renamed the “Galena River” after the Galena ore that was found and mined here.

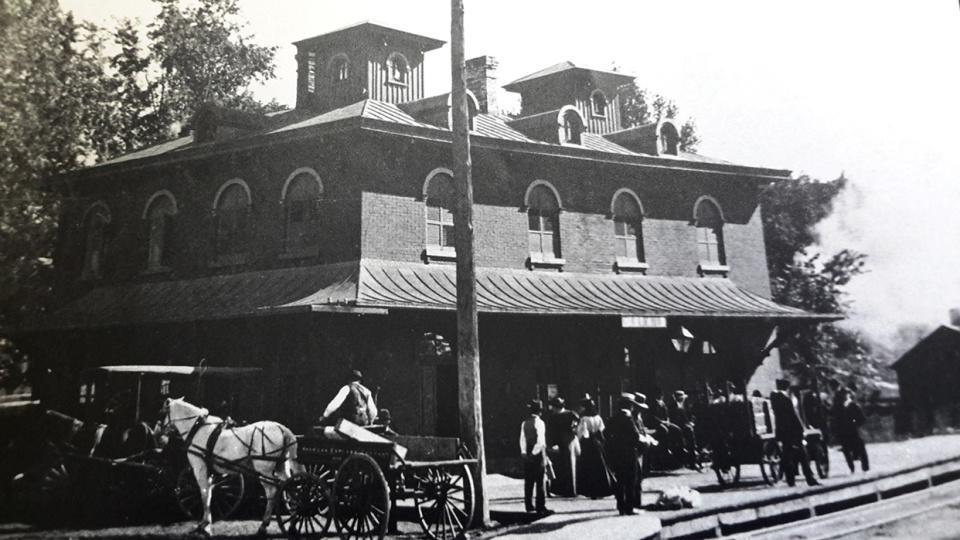

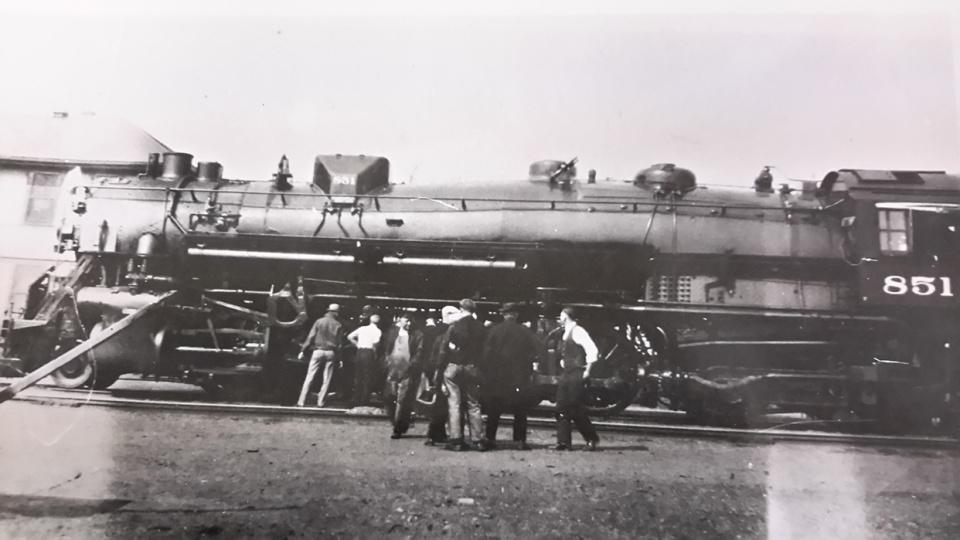

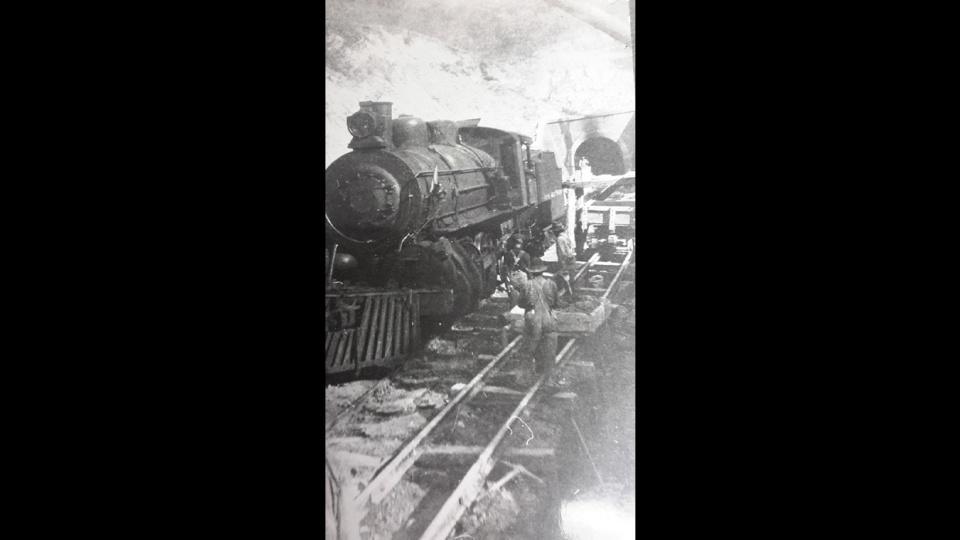

The Illinois Central’s “Iron Horse” first thundered into Galena on November 8, 1854. This marked the end of Galena’s “steamboat” days. In early November of 1854, a grand celebration was given at Galena’s DeSoto House in honor of the completion of the railroad to Galena, even though the DeSoto House did not officially open until six months later on April 9, 1855.

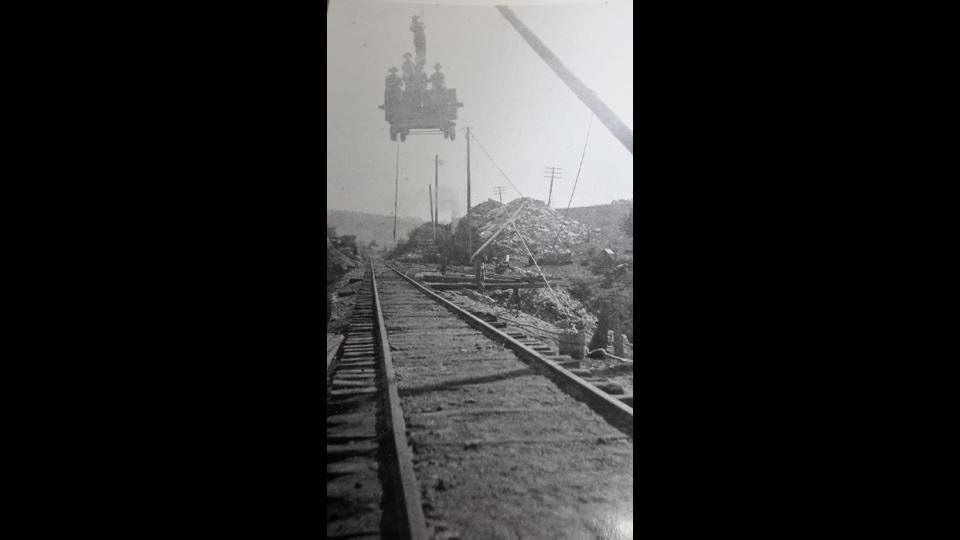

In May, the Galena Daily Advertiser stated: “Yesterday forenoon, about half past 9 o’clock, the first locomotive, with the construction train of the Illinois Central Railroad, crossed the Galena River, on the handsome bridge built for that purpose. The train moved slowly to test the structure, which was fully adequate to the weight brought to bear upon it.”

With the arrival of the Illinois Central, a new railroad depot was constructed in 1857, which you will learn about on the East Side Tour.

But the arrival of the railroad and its construction to the Mississippi, opposite Dubuque, was the death blow to any hopes Galena may have entertained for future growth and prosperity. The railroads would soon kill both the steamboats and the stage lines. The latter in 1857 had 15 stage lines arriving and departing from the city.

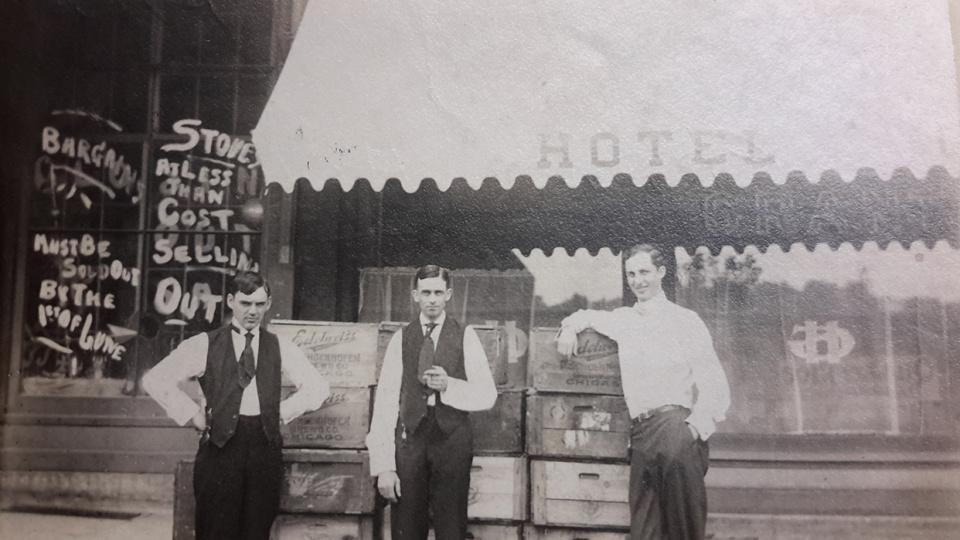

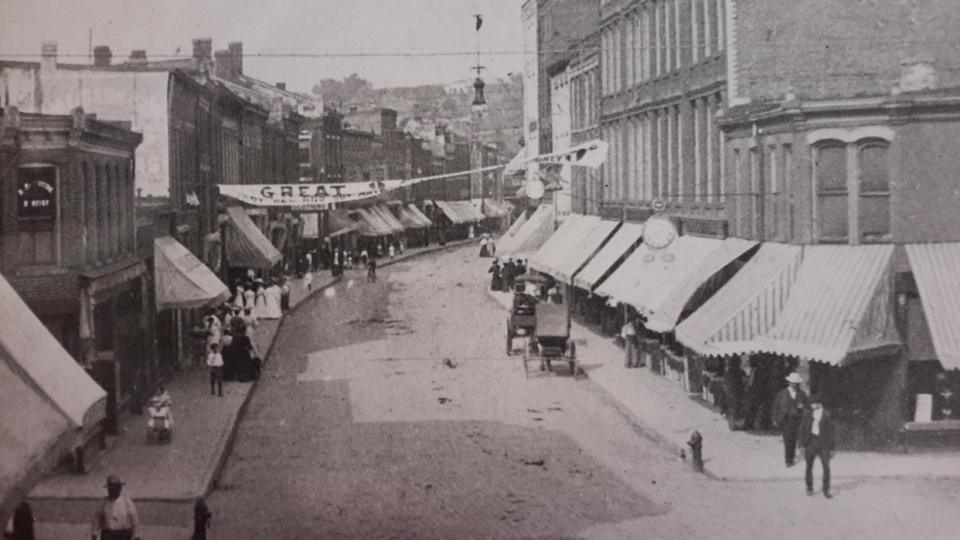

Galena’s business activity peaked in 1857, when its population was estimated to be between 12 and 14 thousand. However, as a result of a nationwide depression, called the Panic of 1857, Galena’s businesses were hit hard, as were property values. Property which had cost $23,000 was sold for $6,000, and on Main Street stores which had cost $7,500 were going for $1,500. Some Main Street rents had fallen from $1,000 to $180 annually. The city’s total assessment had fallen from $1,500,000 in 1857 to $450,000 in 1867, a mere ten years later.

Nearby Dubuque recovered from the Panic and soon surpassed Galena in economic activity. This “Key City” of Iowa did not let Galena forget this fact. In 1858 a Dubuque editor referred to Galena as the “Niobe of the West,” pointing out that Dubuque was shipping to Galena on the Galena Packets because the St. Louis boats found it “inconvenient to go out of their way in order to reach Galena.” Two years later, in 1860, Dubuque poked more fun at Galena and branded her as an “inland town” because the steamboat W.L. Ewing had been unable to get up the Galena River on account of the mud.

By 1860 the population had dropped to about 10,000, and it continued to decrease to an estimated 7,300 people by 1870 and to 5,000 by 1900.

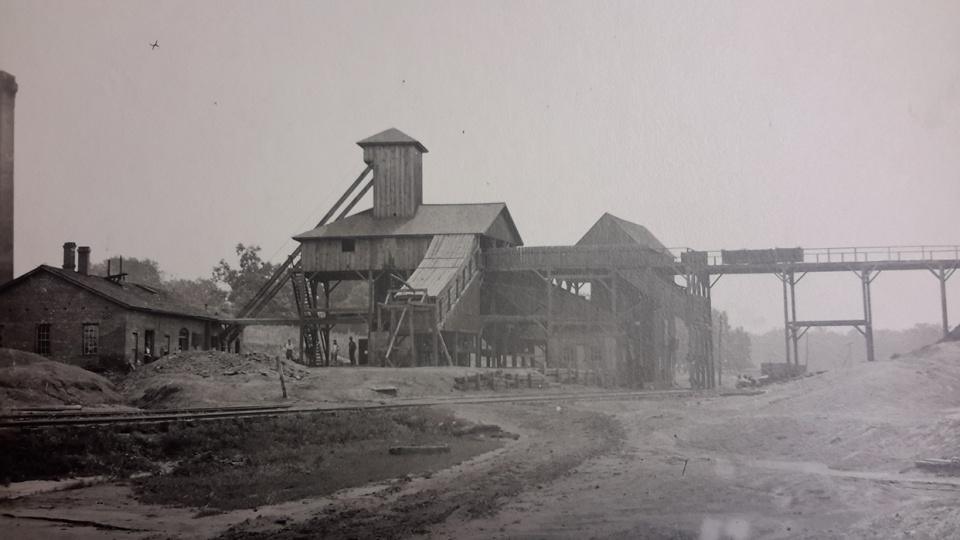

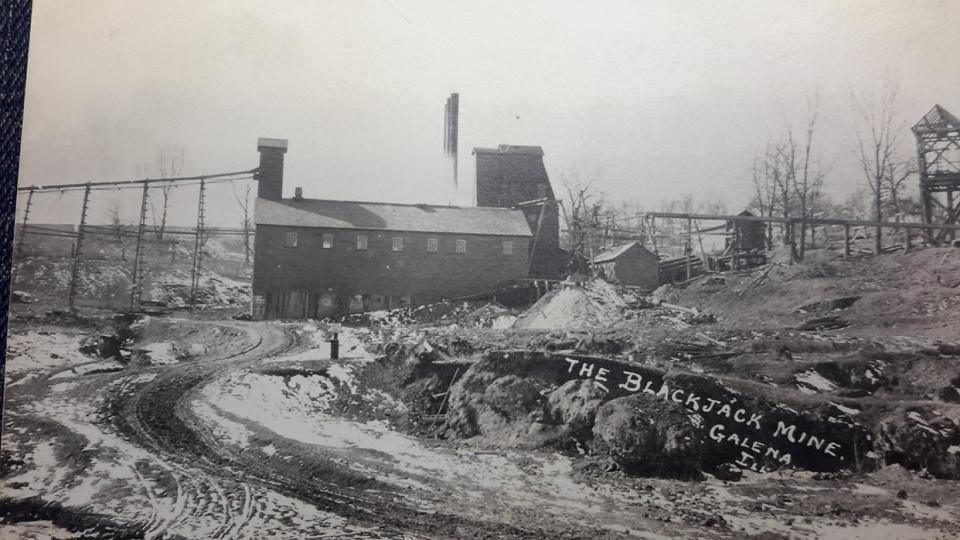

In the 1870’s new mines were being discovered further west. These new mining adventures, along with the rising costs of mining, affected the commercial importance of Galena’s lead mines.

However, Galena was still enjoying some prosperity in the 1890’s. In addition to all of the earlier businesses, Galena now boasted four railroads transporting goods with trackage through Galena. They were the Illinois Central, Chicago & Northwestern, Chicago Burlington & Northern, and the Chicago Great Western, with the last passenger train departing from the Depot in 1972.

During the 1890’s there was also a packing house slaughtering about 1,500 hogs a day; several cigar factories; a sash, door, and blind factory; a monument and marble works; a knitting factory; two manufacturing jewelers; a sawmill; a smelter with a capacity of 42,000 pounds a week; and a broom factory.

In 1890, in one of several efforts to revive river transportation, a Government dredging fleet removed the silt from the Galena River, and locks and a dam were erected below the city. Galena citizens were optimistic about Galena’s future. The dam was financed by private capital but was purchased by the US Government in 1894. However, the locks were removed and the project abandoned in 1922, when Galena resigned herself to the river’s inability for navigation. It has not floated a freight barge since 1916.

That optimism Galena citizens had in 1890 didn’t last long. In 1893 there was another nation-wide depression. Galena was hit hard and the economy deteriorated. There was a sharp decline in the demand for lead and zinc. Galena spiraled into a period of decay as other towns siphoned off her trade. Because money was scarce, many of the buildings were left untouched. Vacant buildings became homes for pigeons and rodents. The never ending task of dredging the river was given up, and the Galena River became a trickle compared to earlier days. Unfortunately, the city never recovered its grandeur. It became just another small, largely agricultural, trade center. To such an end came the “Port of Galena.” Once acclaimed as the mighty commercial emporium of the Northwest, the home of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and eight other Civil War Generals, the community made famous by visits of Abraham Lincoln and other notable people, the chief port of call for scores of steamboats from points as far flung as Pittsburg and New Orleans, this once flourishing metropolis had dwindled to 3,878 inhabitants by 1930.