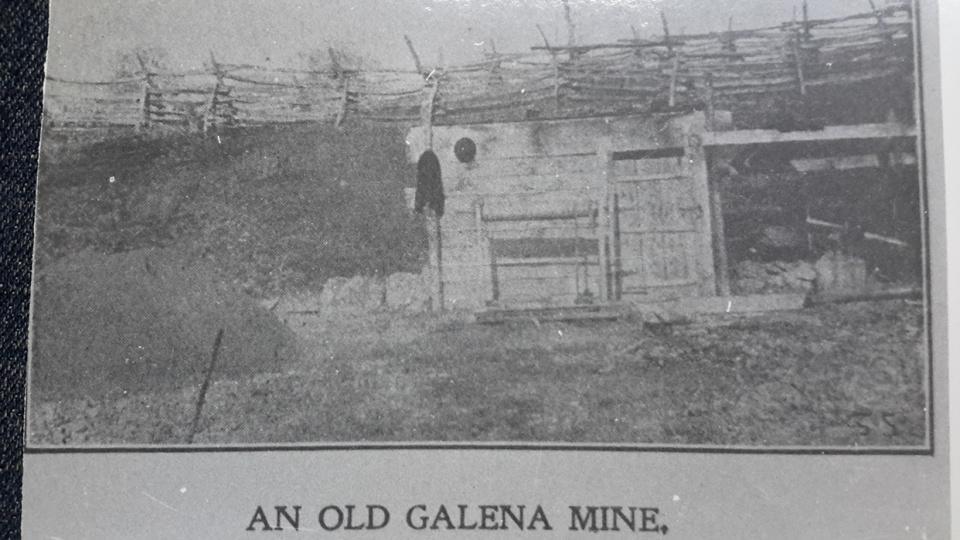

It is not known exactly when lead was first mined in the Galena region, but Nicholas Perrot, a French trader, is credited with being the first white person to see Indian mines around 1690. The native peoples called the area Manitoumi or “the Land of God.” They used the lead ore for charms, body paint, and an item to trade. Most of the workers were women, children, and old men; the braves did the hunting and fishing. They kept their mines well-hidden for many years to discourage white settlers, whom they did not trust. They didn’t have sophisticated equipment; therefore, they just worked the deposits that were close to the surface using deer horns and other crude tools.

While lead from the region had been a trade item for thousands of years, the Fox and Sauk tribes were the ones most associated with the activity upon the arrival of the French, British, and Americans. It was LaSueur who entered a tributary of the Mississippi River known as LaFevre River. The French were thought to have called the river the Feve, (pronounced fave) or bean, because of wild beans growing along the banks, but the exact meaning of the word was—and remains—somewhat of a mystery. It was later translated to Fever until concerned residents thought it wasn’t a good name to draw settlers. In 1854, the State Legislature officially renamed it the “Galena River,” which is Latin for lead sulfide. But where the stream originates in Wisconsin, it is still called the Fever River.

When LaSueur returned to France, he described his discovery in a report called the “River of Mines.” The Frenchmen returned and soon taught the Indians how valuable the ore was. They also showed them better ways to mine and smelt it. They supplied better tools and various other trade goods in exchange for the mineral. One of these Frenchmen was Julien Dubuque, who came to the area in 1788 and established a trading center among the Sauk and Fox Indians near the present town of Dubuque, Iowa, which bears his name. His first mining operations were on the west bank of the Mississippi River where the city of Dubuque is located. The Fox, especially, greatly respected him and granted him the freedom to mine freely and safely throughout the surrounding area. He died in 1810 and was buried one mile south of Dubuque. Once a year, the Fox Indians visited his burial-place, performing religious ceremonies at the site.

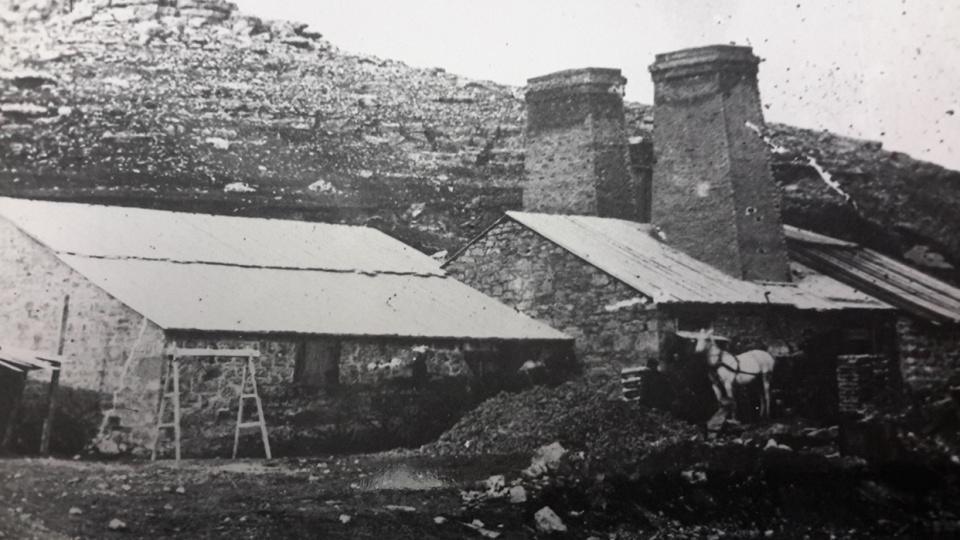

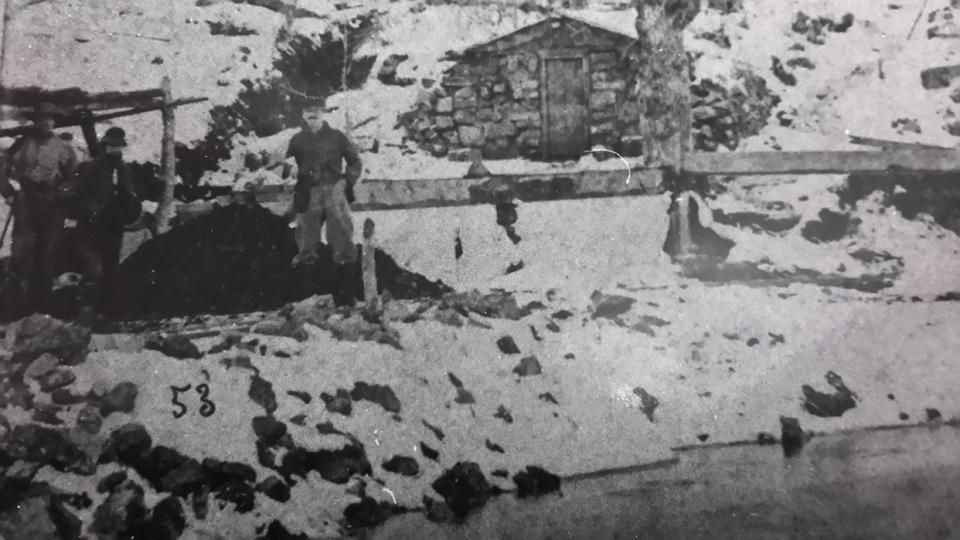

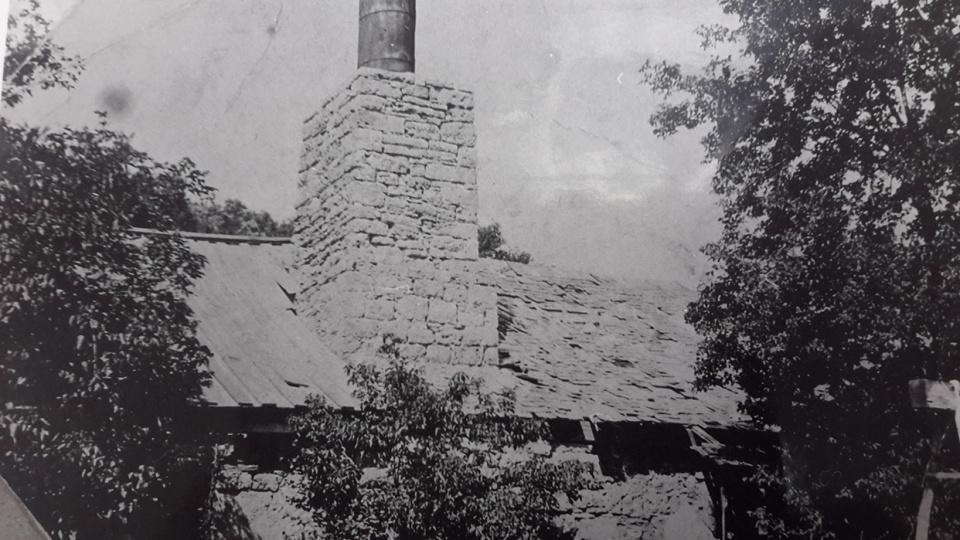

By 1815, the Dubuque mines on the east side of the river had been worked for almost 37 years, but still only 20 crude Indian smelting furnaces were operating in the Galena area. The Indian mode of smelting was unsophisticated. They built a stone furnace which consisted of a hole lined with stones and dug into the hillside about two feet deep and two feet wide. A trench, filled with dry wood and brush, was dug from the sloping ground inward to the bottom of the hole. The trench was filled with ore and the fuel ignited, and in a few minutes the molten lead fell through the stones at the bottom of the hole and drained through the trench. The fluid mass was then poured into a crude mold. As it cooled, it was called a “plat.” A “plat,” or bar, weighed about 70 pounds, which is close to the weight of the miners’ “pig.”

Julien Dubuque was soon replaced by both private traders and government agents. It has been reported that George Davenport, a trader based downstream at Rock Island’s Fort Armstrong, successfully shipped Galena’s first boatload of lead ore down the Mississippi River in 1816. This shipment was in payment for various trade goods.

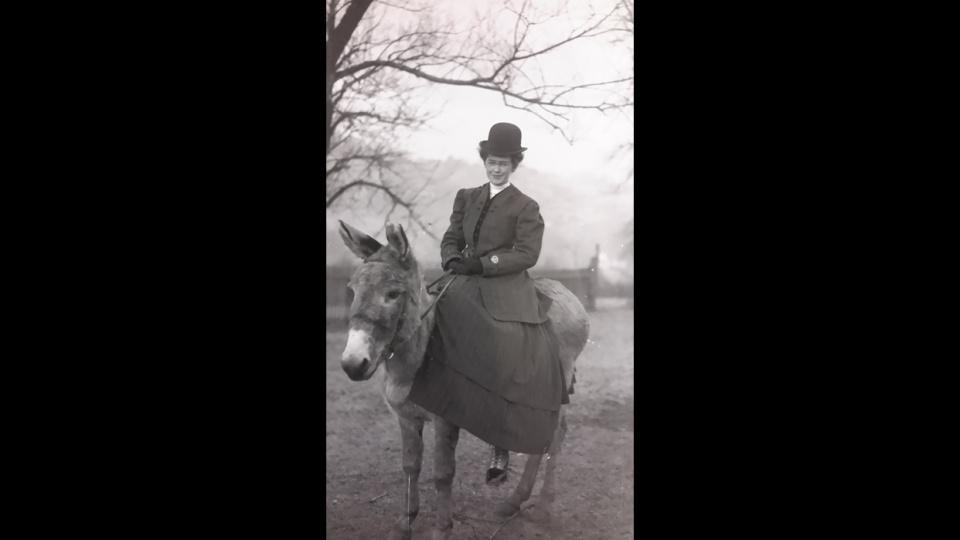

In 1818, the first white settlers came to mine the rich deposits of lead. They did so illegally—the first leases were not issued by the federal government until 1822. During the first few years, many traveled up the Mississippi in the very early spring, after the river thawed, and then down again in the late fall, before the river froze. They were called “suckers” after the migratory fish that traveled at the same time and season. According to legend, Illinois was then nicknamed “the Sucker State” because of the Galena miners migrating like the sucker fish. Early miners from Wisconsin were nicknamed “Badgers” since their “hardscrabble” diggings were compared to the burrowing of the native badger, which became the mascot of the State of Wisconsin and later the University of Wisconsin.

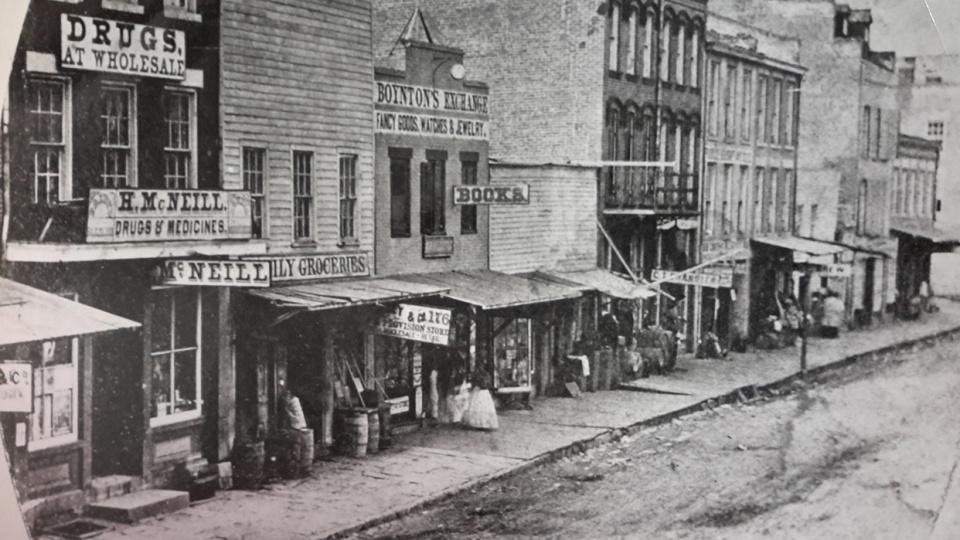

The largest discovery of lead ore made at this time was about one-half mile above Galena. It was called the “Buck Lead,” and proved very rich. Word of this and other finds spread rapidly. Prior to 1820, modern-day Galena was a smattering of Fox and Sauk Indians, miners, smelters, and white traders. It was called “La Pointe.” They lived in crude homes, some with sod roofs, log cabins, shacks, and tents.

In the spring of 1820 the settlement’s first white woman arrived when the Thomas Januarys came from Kentucky and built their log cabin on what is now January’s Point in the north part of the settlement. Mrs. January must have had the spirit of endurance and courage to be willing to face Indian warfare and forego all life’s comforts. Soon January’s Point became the center of the growing community. One by one, log cabins were built near the post and on the river bank. For two years these pioneers were isolated from the outside world with only the natives, prospectors, and a few settlers as their companions.